...to embody Christian faith and discipleship...

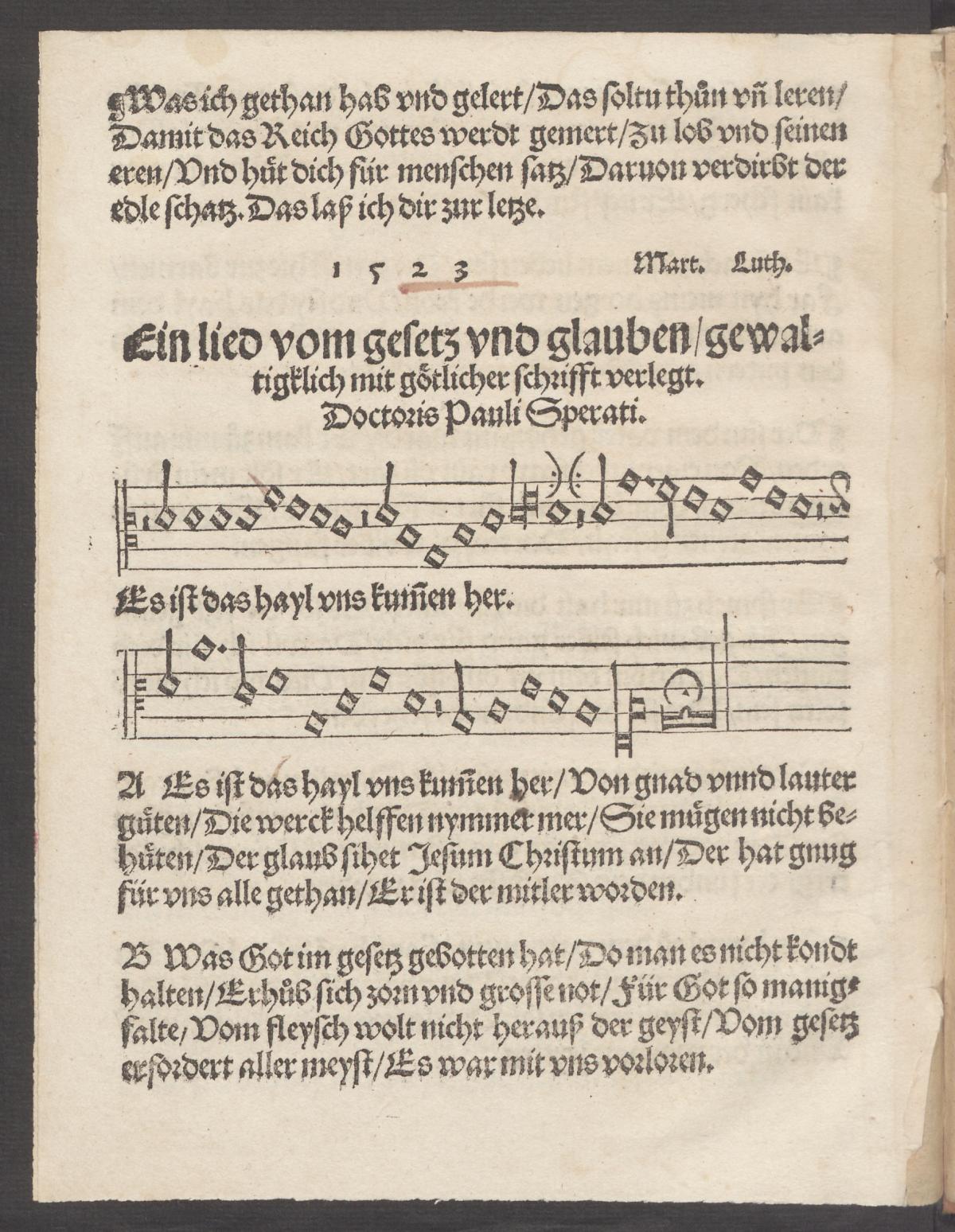

through music

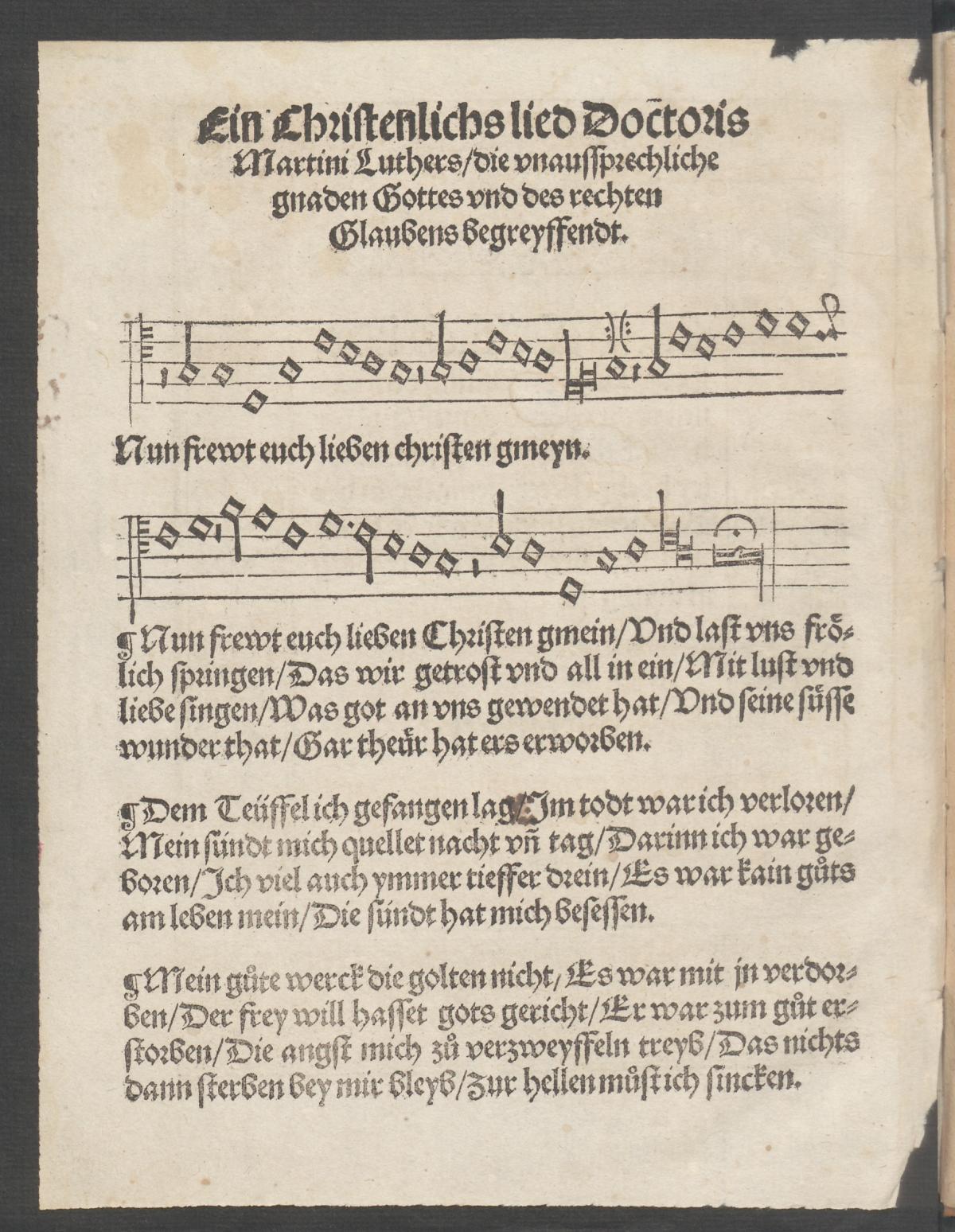

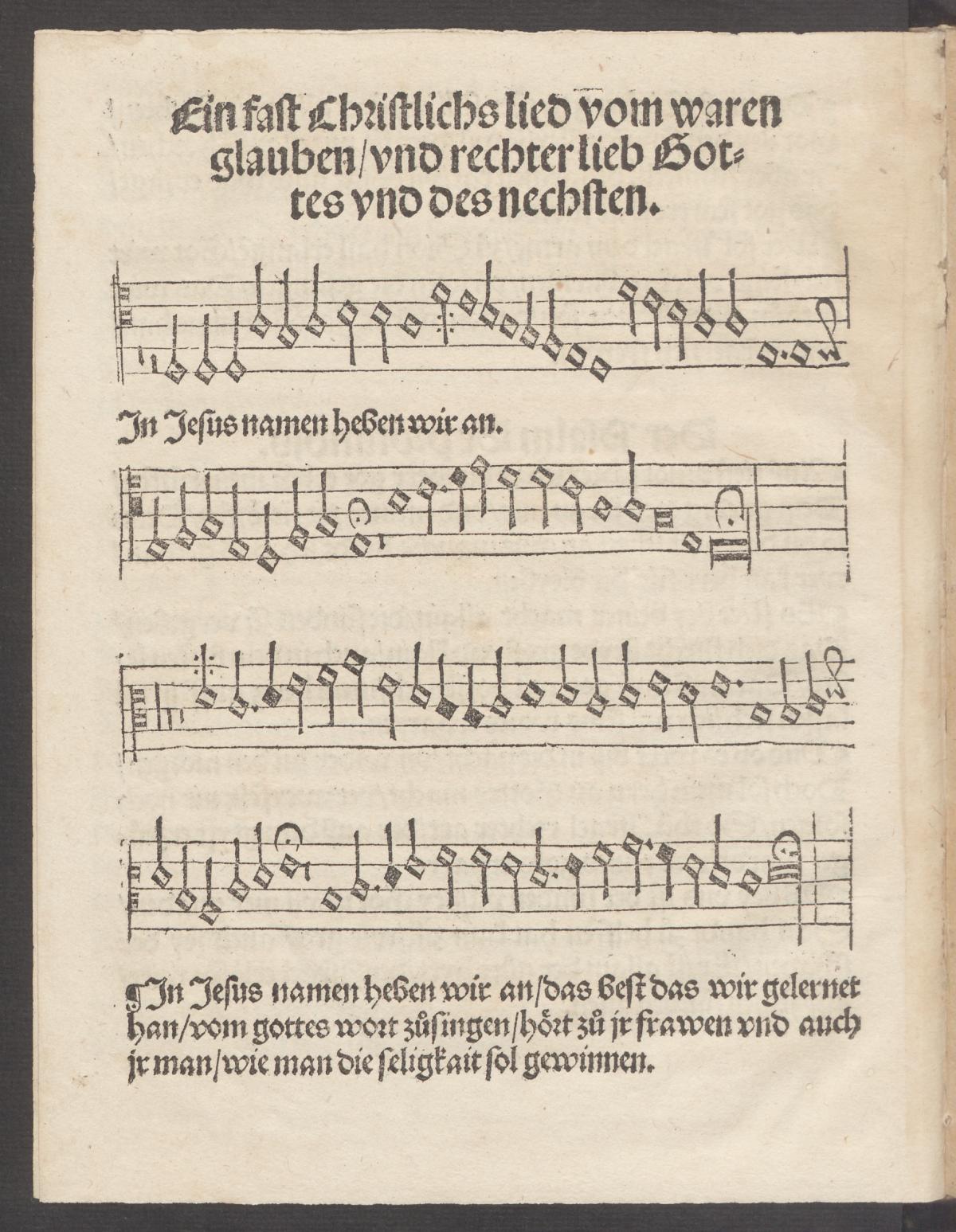

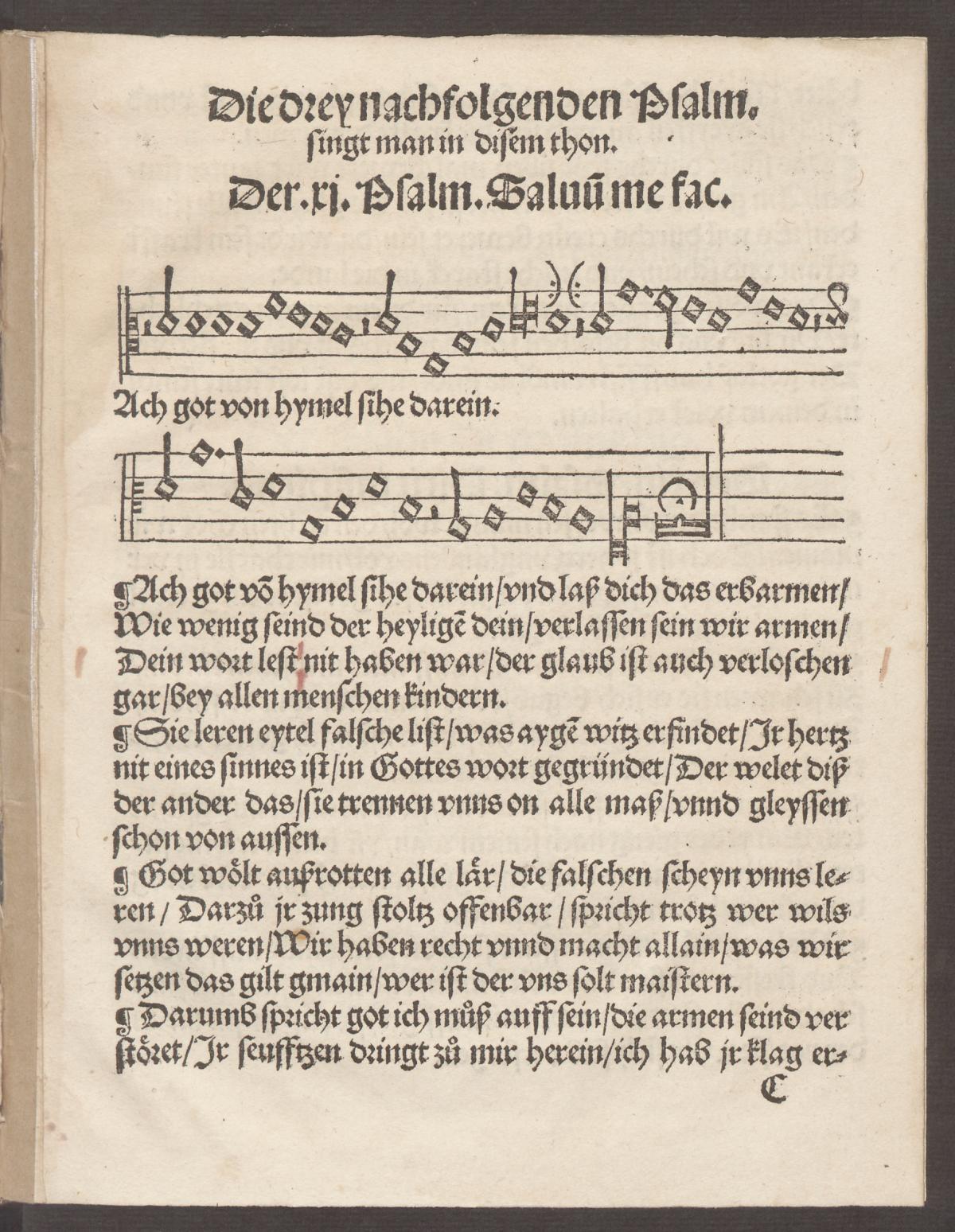

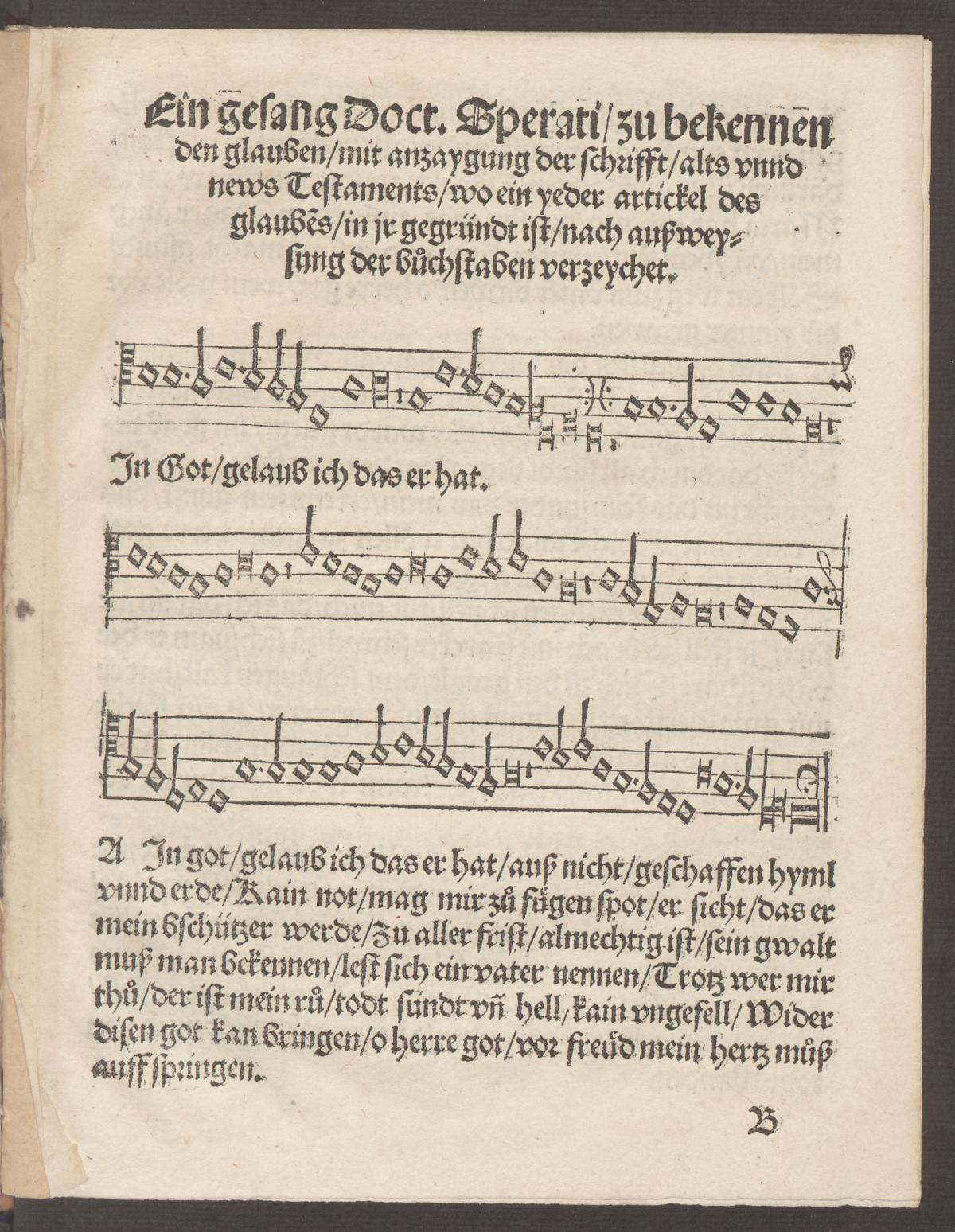

Luther´s reforms of the Latin Mass in 1523 and 1526 and the first hymnals of 1524 shaped the spiritual identity of the faithful in Wittenberg, but also triggered far-reaching developments in the world of music in the decades and centuries that followed.

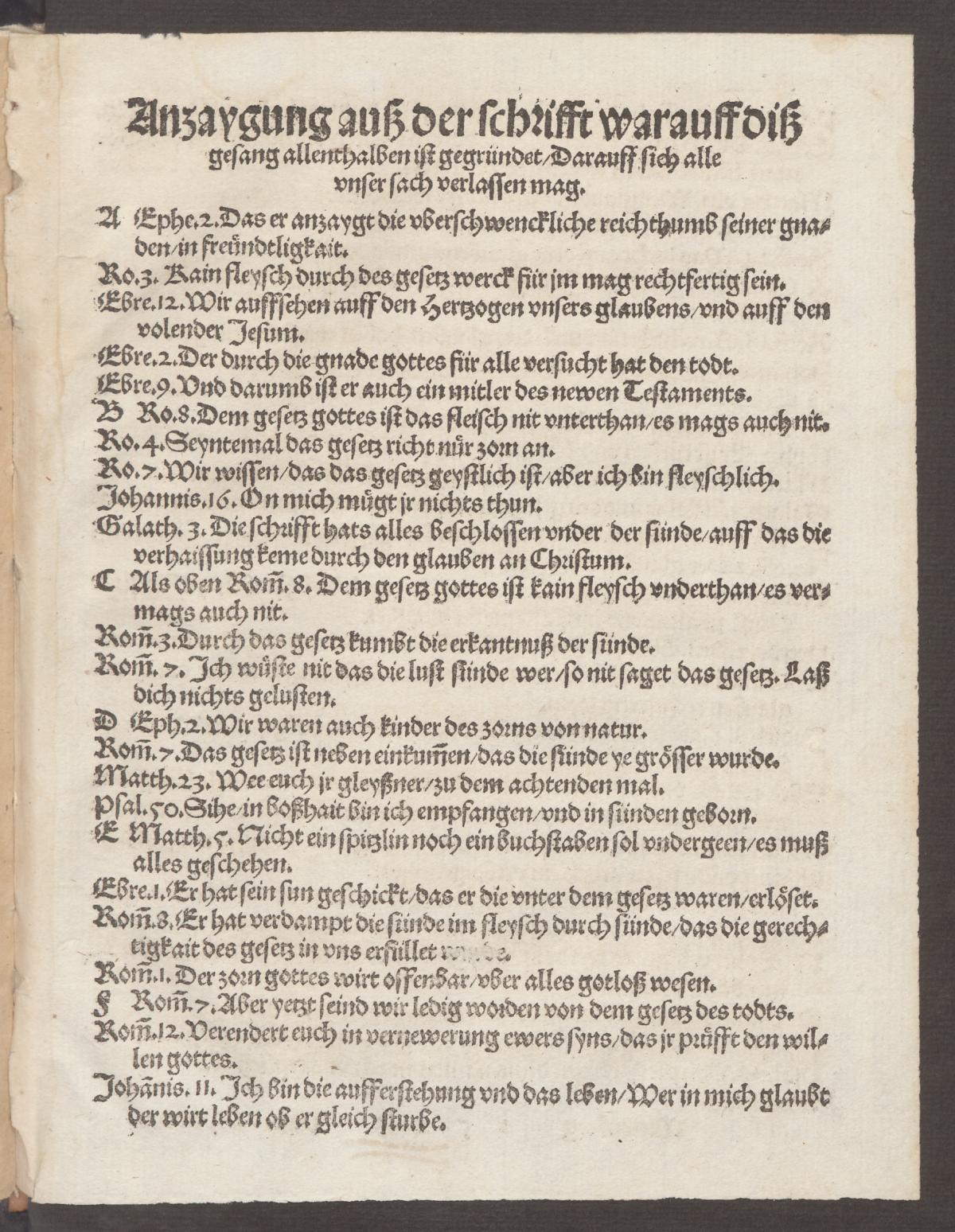

Luther's Sola Scriptura emphasized individual freedom in understanding the Bible independent of the power of church authorities and placed German as the liturgical language of the

Reformation movement, which in subsequent centuries led to the freedom of composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach to interpret the Luther Bible and Luther´s chorales in his own musical theology

through his cantatas and passion music.

Thus, Luther's musical and liturgical heritage offers a unique Christian perspective on the cultural transformation processes of the Reformation period, which can be understood as a consequence

of Humanism and the Renaissance, and at the same time as a catalyst for the design of an image of the self-determined, ethically responsible human in the tradition of Lutheran anthropology.

Luther's view of humanity and its relationship to the sacred and to the natural world which shaped the liturgies of the Reformation exists today more than ever in tension to the diverse

approaches to the meaning of human identity. Nevertheless, this unites us all today as well with Luther's time, as both represent eras of fundamental cultural transformations with the emergence

of multiple new ways of understanding ourselves and the world.

»Luther's view of humanity and its relationship to the sacred and to the natural world which shaped the liturgies of the Reformation, exists today more than ever in tension to the diverse approaches to the meaning of human identity. Like Luther, we experience multiple new ways of understanding ourselves and the world - how do they sound?«

Luther sees music as an intrinsic part of creation, and it is therefore also part of all living things. For Luther, music bears a dual nature between accessibility and withdrawal and the

categorization into natural and artificial music has important consequences for the use of music in the proclamation of the Christian faith in the liturgy. Luther trusted music in its artful

performance to open up an additional space of religious experience, especially for the interpreters and the expert listeners, and to point directly (behind its sound) to God. This profound trust

in pure sound and in the artful making of music may also have led to the fact that Luther, unlike Calvin or Zwingli, did not oppose instrumental music or the organ in liturgy.

In addition to his commitment to artful music, Luther encouraged the integration of popular melodies and German lyrics into worship songs so that the congregation could understand the meaning of

the songs and discover in music a language that gave expression to their religiosity without the mediation of church authority-especially outside the churches. This revolutionary approach to

communal singing at home, at the kitchen table, as Luther hoped, fostered a new space for transformational experiences: singing together means breathing together, listening to one another, and

being called into the "here and now." Thus, it involved the complex process of a form and content transformation that had the goal of creating and affirming an identity for believers

(collectively and individually); liturgy was to "embody" Christian faith and discipleship in Christ.

The Global Songbook 2024 picks up on these transformational movements and collects music which have become established only in recent decades in the global Lutheran community. Musicological and liturgical case studies of selected liturgies and songs from all seven world regions of Lutheranism as well as discussions of transformational processes of the Lutheran liturgical heritage compliment in an additional theory section the publication.

Africa

Angola. Botswana, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia. Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique,

Namibia, Nigeria, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Asia

Australia, Bangladesh, Holy Land, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka,

Taiwan, Thailand

Central Eastern Europe

Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia

Central Western Europe

Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland, United Kingdom

Latin America and the Caribbean

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela

Nordic Countries

Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden

North America

Canada, United States